|

| My husband and I in front of the Trevi Fountain in Rome. |

Have you ever visited a place for the first time and

felt as though you were finally at home?

That's what it was like for me when I first set foot

in Italy. And—more incredibly—it's felt that way every time I've been fortunate

enough to travel there. I'd expected the magic to wear off after a visit or

two, due to familiarity or the added perspective of age, but it's remained

constant through the years...like my love of Renaissance art, Murano glass

beads, or freshly made chocolate-orange gelato. (For the record, Festival del Gelato in

Florence is my favorite gelateria in the world!)

Then again, maybe I'm biased because I'd daydreamed

about taking a trip to the famous cities of Venice, Florence, and Rome ever

since I was a little kid. Or possibly because our close family friends were

native Sicilians. Or because my dad had spent a memorable summer working in

that country before he met my mom, and I grew up hearing

stories of Italy's beauty. Or maybe it's just because I really love ravioli,

passionately sung music, Mediterranean shorelines, and pure southern European sunshine.

|

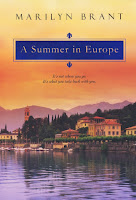

| "Marilyn Brant's A SUMMER IN EUROPE is a wonderful tale that captivates readers as Gwen, transformed by her surroundings, undergoes a change of heart about life... and love." ~Doubleday Book Club |

I poured my love and first impressions of Italy into

a novel called A Summer in Europe (Kensington, 2011). The main character, Gwen,

takes her first trip abroad with her eccentric aunt Bea and the elderly lady's outspoken

Sudoku & Mahjongg playing friends. The adventure opens Gwen's eyes to

the wonderful transformative power of travel and getting to see the world

through a new lens at long last. It's a happy story of a woman who's on an inward

journey as much as an outward one—though, of course, she doesn't know that at

first.

What's always intriguing to me about travel is that,

even when we know a trip has the power to change us, I don't think it's

possible for us to truly recognize that change happening until we're at least halfway

through it. Or maybe even home again...

I remember being sixteen and an AFS exchange student

in Brisbane, Australia. I couldn't believe I'd been lucky enough to be chosen

for this dream placement. (The residents often called it a "sun-burned" country, but I just called it "gorgeous," especially with sites like the Sydney

Opera House, the Gold Coast, the Great Barrier Reef, and real live koalas that

I could hold...) I'd read the student-exchange materials with tremendous

interest. All of those handouts and brochures that the organizers had sent

us—not just about the host country, but also about the time we'd be spending

with our host families and our host schools. We were cautioned that we would

need to change and adapt to our new environment. That there would be a lot of

information to process. That it would be a roller coaster of emotions.

And it was.

Somewhere in the middle of my summer (their winter)

stay, I wrote in my trip journal that I was supposed to have changed from all

of this, right? Hey, I'd entered into this journey being open to change. I'd

expected it. So, why hadn't it happened yet? I felt almost exactly the same as

when I'd left home. To my own eye, I was still this mostly geeky, sort of awkward high-school

girl who was good as school stuff and not entirely comfortable with much else.

It was only in retrospect—some months after I gotten back—that I could

see in hindsight that there had been changes all along. Some were subtle shifts

in perception. Others were massive worldview transformations that, ultimately,

ended up altering the course of my career path and my life.

|

| "Gelato" Photo by Aaron Logan, courtesy of Wikimedia/Creative Commons http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Gelato.jpg |

I think a strong setting—whether it's in 3D right before our

eyes or simply described on the page with heart and an acute attention to

detail—has the power to affect as much change upon us and/or our protagonists as

any other real-life person or fictional character could. It's the very air we're

breathing. The sounds we're hearing. The landmarks in our periphery. And the

taste (oh, the delightful taste!) of our most unforgettable dessert.

What's a setting that's left a life-long impression

upon you? A place that made you feel at home?

~~~

Marilyn Brant is a USA TODAY bestselling author of contemporary women's fiction, romantic comedy, and mystery. She was named the Author of the Year (2013) by the Illinois Association of Teachers of English. She loves all things Jane Austen, has a passion for Sherlock Holmes, is a travel addict and a music junkie, and lives on chocolate and gelato. If you want to see pictures from her European travel adventures, she has a page on her website HERE. And, in her latest novel, The Road to You, her characters take a road trip down Historic Route 66, and she has photos HERE from that journey as well :) .